If you are still running jessie you probably noticed that the jessie-updates and jessie-backports suites have been removed from mirrors, because you got those error messages:

W: Failed to fetch http://ftp.debian.org/debian/dists/jessie-updates/main/binary-amd64/Packages 404 Not Found [IP: 130.89.148.12 80] W: Failed to fetch http://ftp.debian.org/debian/dists/jessie-backports/main/binary-amd64/Packages 404 Not Found [IP: 130.89.148.12 80]

I was not involved in that decision (which was made by the FTP masters team), but since there is some confusion around it, I will try to give my understanding of the resulting issues.

The typical /etc/apt/sources.list file for a jessie system with backports enabled is:

deb http://ftp.debian.org/debian jessie main deb-src http://ftp.debian.org/debian jessie main deb http://security.debian.org/debian-security jessie/updates main deb-src http://security.debian.org/debian-security jessie/updates main deb http://ftp.debian.org/debian jessie-updates main deb-src http://ftp.debian.org/debian jessie-updates main deb http://ftp.debian.org/debian/ jessie-backports main contrib non-free deb-src http://ftp.debian.org/debian/ jessie-backports main contrib non-free

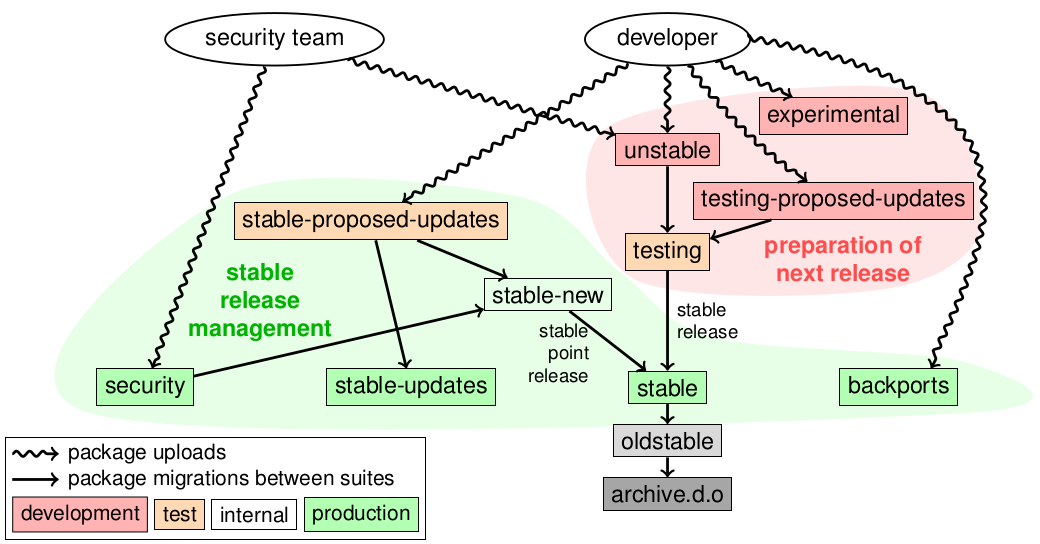

Debian packages are distributed using suites (which can be understood as channels). The global picture looks like this:

(This is slide 42 of the Debian Packaging Tutorial.)

deb http://deb.debian.org/debian jessie main is the easy one. It contains the bulk of packages. It is initialized by copying the content of the testing suite when a new stable release happens, approximately every two years. It is then updated from stable-new (an internal suite) when stable point releases happen (see below).

deb http://security.debian.org/debian-security jessie/updates main is the security suite in the figure above. It is used by the Debian security team to provide security updates. They are announced on the debian-security-announce mailing list.

deb http://ftp.debian.org/debian jessie-updates main (stable-updates above) is a suite used to distribute important updates that are unrelated to security, and that cannot wait the next stable point release. They are announced on the debian-stable-announce mailing list. Interestingly, a large proportion of those updates are related to changes to daylight-saving-time rules that are sometimes made very late by some countries.

stable point releases happen every few months (see for example the Debian 8.11 stable point release). They consist in updating the stable suite by copying important updates that were submitted to stable-proposed-updates. Security updates are also included.

backports follow an entirely different path. They are new versions of packages, based on the version currently in the testing suite. See the backports team website.

So, what happened?

In June 2018…

Debian 8.11 (in June 2018) was the final update for Debian 8. As stated in its announcement:

After this point release, Debian's Security and Release Teams will no longer be producing updates for Debian 8. Users wishing to continue to receive security support should upgrade to Debian 9, or see https://wiki.debian.org/LTS for details about the subset of architectures and packages covered by the Long Term Support project.

In other words: jessie and jessie-updates won’t receive any update. The only updates will be through the security suite, by the Debian Long Term Support project.

At about the same time (I think – I could not find an announcement — Update: announcement), the maintenance of backports for jessie was also stopped. Which makes sense, because the backports team provides backports for the current release, and stretch was released in June 2017.

In March 2019…

The FTP masters team decided to remove the jessie-updates and jessie-backports suite from the mirrors. This was announced on debian-devel-announce, resulting in the errors quoted above.

How to solve this?

For the jessie-updates suite, you can simply remove it from your /etc/apt/sources.list. It is useless, because all packages that were in jessie-updates were merged into jessie when Debian 8.11 was released.

The jessie-backports suite was archived on archive.debian.org, so you can use:

deb http://archive.debian.org/debian/ jessie-backports main contrib non-free deb-src http://archive.debian.org/debian/ jessie-backports main contrib non-free

But then you will run into another issue:

E: Release file for http://archive.debian.org/debian/dists/jessie-backports/InRelease is expired (invalid since 36d 1h 9min 51s). Updates for this repository will not be applied.

Unfortunately, with the APT version in jessie, this cannot be ignored on a per source basis (it can with the APT version from stretch, using the deb [check-valid-until=no] ... syntax). So you need to disable this check globally, using:

echo 'Acquire::Check-Valid-Until no;' > /etc/apt/apt.conf.d/99no-check-valid-until

After that, apt-get update just works.

(There are some discussions about resurrecting the jessie-updates suite to avoid the above errors, but it is probably getting less and less useful as time passes.)